- Home

- Dan Chiasson

The Math Campers Page 2

The Math Campers Read online

Page 2

He had a strange and vivid dream. He was driving in the country, on winding roads near his childhood home in Vermont. In the darkness, he struck what he believed was a deer.

When he pulled over, he discovered a short, bearded man with a pointed hat, dead in a ditch by the roadside.

He knew instantly that he had killed a troll, the sort of cartoon troll who dwells under bridges in storybooks.

He piled the troll’s body into the trunk of his car.

Some miles down the road, distressed by the accident, he again struck what he believed to be a deer.

When he stopped his car, he discovered, dead by the side of the road, the body of the poet Robert Lowell. He loved Lowell’s work and had long fantasized about meeting him. He once asked his friend Frank, who had been Lowell’s protégé, if Lowell would have liked talking to him. Frank seemed to wince, but suggested that yes, perhaps Lowell would have.

He put Lowell’s large body into the trunk of his car, next to the compact body of the troll.

Some miles down the road, on an especially dark stretch of highway, he again struck a heavy object or body with his car. He stopped, and there beside the road was the body of a stranger. The stranger was a young man, perhaps twenty-five, though he was badly disfigured by the force of the impact. He put the stranger’s body in the trunk of his car, on top of Lowell and the troll.

With the stranger, Lowell, and the troll in the back of his car, he drove through the night, the horrible weight of his actions settling upon him. In the dream, he was looking for a place to bury or hide the bodies; which, when he awoke, he understood to be his dream’s own management of time, consciousness, and guilt.

When he awoke, there were no bodies to dispose of. But he had a dream he needed to interpret.

In the swivel chair where JM wrote, he wrote he wrote:

“In the swivel chair where JM wrote

I read an inscription

from our mutual friend: For James,

who is a great poet—Love, Frank.”

Later that night, he wrote to Frank:

“I am in Merrill’s apartment for a residency and found several books of yours on the shelf, which you’d inscribed for him in the seventies and eighties.”

Later that night, Frank wrote back:

“One more world buoyed by talent and money, gone—to have what you always effortlessly found to be there, gone.”

Later that night, he remembered a time in high school when he and his friends partied in the woods on a frigid March night:

“We lit the forest up fucked up!

then two by two, whoever was who,

sought out the dry and grassy ground—

bare-assed, you first, then I will follow.”

Like youths in a Shakespearean pastoral, they sought out woods for leisure. But the woods there were frightening, full of ravines and chasms and gorges, and every year someone, usually a tourist, fell; and the pall of depression fell in every dark corner, and in every household of everyone in those days in northern Vermont, including, he told me, his own.

He was leaving, he said, a blank in this stanza:

“I’m leaving a blank in this stanza

until the neighbor’s flashlight

peers into the heart of things:

[ ]”

A stanza, he wrote, which would be undone if ever it was done, defeated if he ever succeeded in finishing it.

Deleted, rewritten.

Before the correspondence slowed that fall, he wrote a series of letters about transformations he had witnessed. For the first time, he told me he had two sons; he told me about changes in their lives as they grew older, and changes in his own body, as he approached fifty. These letters were somber, sometimes hard to follow, as though the pressure of transformation was too much for him to bear.

Two times he lashed out at me, for merely listening.

In one letter he claimed to know my real name, which was impossible, since I had no real name. I was the channel through which his mind passed, and then I was a gap, an absence, which frightened me.

We worried who had imagined whom, which was futile, because both of us were fundamentally unreal, like contesting realities in a film: we were held, suspended within the larger dream; we alternated coming into, then stepping out of, the light.

The letters would crest with some extraordinary insult against me, which I mirrored back at him. Then he would calm, and the calm became mine; and together we became rather tender and vulnerable, two strangers, alone together in a total, collaborative nonexistence, the happiest and safest place on Earth.

I received the last letter before Christmas. He was going home, to see his mother.

His last letter included a poem he’d written about his sons, “Euphrasy & Rue,” titled after the passage in John Milton’s Paradise Lost which De Quincy had used to describe the feeling of an opium trip.

It was never really in his power to hurt me.

It was painful to imagine that someone I had imagined had imagined me, and could simply stop, leaving me stranded, without oxygen, like an astronaut alone in deep space.

I know he felt the same kinds of fear.

It was painful to know he’d been hit, hard on the face, and then again.

Though afterwards, he was given tea.

It was pleasant to imagine him on a rooftop sunset reading about a rooftop sunset writing about a Sound sideways peach sunset across buoys and yachts.

The day all the water zippered over my father’s head, I knew what being stranded was; my whole life since I’d been stranded, until I dreamed him up; now, since he was gone, I was gone, and since I was gone, he was gone.

“My imagination is a form of forgery,” I wrote, then went to bed.

At dawn he wrote:

“High up all night I thought

of my sons, how when they wake

I will be finishing this poem—

my night their day, my day their night.”

At dawn he wrote:

“Birds, check. First light, sunrise.

This pole vaulting got me down.

My outline splayed on the guest-bed.

Swift captive, tie me up. Bordello bait: tie me up.”

Euphrasy & Rue

Years ago, our sons were born. We named them

Iris and Daffodil. They changed,

one to Euphrasy, and one to Rue;

to Euphrasy and Rue they changed.

To Euphrasy, to Euphrasy, to Rue:

to Euphrasy and Rue they changed.

Years ago, our sons were born;

our sons were born years ago.

On the stereo, we played “Over and Over”

over and over, while all the while upstairs

they changed; we played “Over and Over”

over and over, while all the while they changed.

One by one they replaced the days we’d made

for them with days they’d made.

To Euphrasy and Rue they changed,

they changed to Euphrasy and Rue.

They saw the sadness on the other side

of the horizon, how flowers

blossom, and flash, and fade, remorse

their daily food, and cried.

Our sons were born; the stereo played

“Over and Over” over and over;

they changed to Euphrasy and Rue,

and now they patrol the skies.

II

Q & A

Q: “Over and Over,” over and over?

A: By such lures and enchantments is time stopped.

Q: What part or season of the creation is Tusk?

A: It starts time over; new dream,

repeat, new dream….

Q: As to the creation: where is its refresh button?

A: In a star, in a stock car, on Orion, in the mountains.

Q: My heart is anguish. How can I vanish it?

A: O vanish isn’t a transitive verb.

The song is coming on again: Listen.

[Silence while the song plays.]

[Silence after the song ends.]

[Silence as the song starts up again.]

Whatever Thibault was Thibault is:

like a comet he appears

blazing his stock car through the night sky:

he circles us, a tetherball caught in orbit

while around and around the pole

a dancer remembers her appendectomy

as she lap-dances for a happy bachelor

there by the grace of Fidelity and cocaine.

You see how even change is changed;

a Skylark, stylish and reliable;

you want something to lean on, lean on

remembered swallow, remembered meadow:

our sources say there’s no such place—

rest on the nonexistence

time force-feeds the agastache, alyssum,

when up their little heads they raise

and look around like a periscope, and droop.

Our sources say they leave no trace.

Thunder Road echoes with roars

from the quarry owner’s sons’ RX-7’s;

they drown out the sound of boners going Boing

in the Théâtre Superérotique de Québec

where the dancer spritzes herself and laughs:

another night, another dent in the appendectomy.

So change is changed, the most powerful force

is powerless, it goes on and on;

logic will not protect you, you have to have

stock cars, a rash, false indigo, a rumor.

By the way: I know what you know about me.

And by I, I mean me, the author, Dan:

I know you know what I did, you spread it:

I mean the innermost you and me—

the ones inside our brains. I’ll have my revenge

in the form of blossoming amsonia,

amnesiac Orions with their belts undone,

a hit list, a who’s who, a spritz, a marquis.

Tom the stutterer’s brother

had the backhand.

We were doubles partners

deep inside the quarry.

Camel’s Hump was frozen

on the horizon

snapped mid-undulation.

Everyone died climbing it.

La Tulip: the feared, hated,

later embezzler of electricity:

he smashed a fucking asteroid

past my racket, to Quebec.

Mike’s Civic bazookaed Ratt

to cross-bias La Tulip:

party sled, hedonistic pod,

our papers in the glove box….

glow-lit, post-match, we drift

all the way, apparently, to

bug zappers, thunder, G & R. The Strebels

cough haze and wheeze in the back.

Now the way becomes time,

and we are still drifting

fresh from a slaughter,

west, west, west, and west

to a party in a cattle pasture,

the cattle vaguely suspect.

Mike’s father, as you know, deals

in prize semen. All of this turns out

to be made of paper. Imagine:

Post-its, notes-to-self,

emotionless as origami.

Even the backhand, even the match.

Who changed change, die, eightball, tarot, oracle?

Who put the flux in flux? It was my go-to

when the slipstream slowed to a trickle, hangover cure,

the reason reason gave the river wonder left behind.

One day I’m looking around in my underwear

for Paulina Porizkova, now I’m the leech gatherer.

Last week I’m carded trying to buy Coppertone,

now I’m mistaken for my own pallbearer.

God made change, Daniel; he made change change,

he made reason reason, bother bother, dust dust.

But why, Sister, why, did he retire before

he made decrease decrease, limit limit?

Paulina Porizkova and I are having a party. Bill Bixby

is dancing with Jo Anne Worley. We’re all very small,

and very hungry, and lonely, since all our friends

are dead. We’re aphids, alone on a dianthus.

…still drifting farther west,

the clouds in sync,

my thoughts in sync,

drifting too, and shadows

cast by thoughts, all farther,

farther west, in sync;

the car, the clouds, the shadows,

my mind parading slowly

from Charlotte to Ferrisburgh

with the lake looking on,

and we were looking

for a homemade sign

we’d find at the end

of the driveway, by the curb:

a party. Earth brought us here

even driving the wrong way

across its slowly turning,

always turning lakes and brooks.

We found the driveway, and

slowly to the party drove….

Q: Then where did Josh True go?

A: Into the maw, the void, the abyss.

Q: By violence, by illness, by neglect?

A: By none of these causes did he go.

Q: Like a god he strode into storms and water?

A: Neither by lightning nor by drowning.

Q: Then by his beauty, and the gods’ jealousy?

A: He looked like Tyne Daly

wearing an antimatter toupee.

He did not die valiantly.

The Earth turned, and he stood still.

Matt crept on Sean

waiting by the stairs

for Sean to re-emerge

from the skylit addition,

the parents’-den, lion’s-den,

this is 1986, with Amy,

an astronaut lost in time,

already headed to oblivion—

Sean led her by the hand,

the backdrop of what happened

not yet having happened,

there/not there, as though on layaway;

here is Matt, you know him,

he’s my Star Catcher: baby-blue

sky-blue, robin’s-egg bike,

the brother who drowned in a pool

and resurfaced as the family narrative?

That Matt. That summer, that poem.

Matt approacheth. Sean, now blown,

apologizes to him: why?

Laughter as they recap every gag

and thrust. Neither had,

but Matt had had, a brother.

Exeunt Sean and Matt.

Amy looks at me as though to say,

You want to go? And leads me

to the skylit addition.

O

utside the party, a pattern

Virgil first identified drives

the cattle, timeless geniuses

of hay and feces, engorged

until it’s time to do their thing:

Mike’s dad squeegees another load

from their zillion-dollar balls,

their mortgaged balls, and overnights

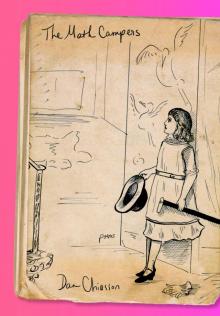

The Math Campers

The Math Campers